Male urethral stricture – The disease is as old as humanity

Urethral stricture is the narrowing of the urethra that restricts urinary flow. The disease is as old as humanity itself. Ancient Indian and Egyptian medical texts describe dilators and catheters, which were used to treat the condition. Their treatment has not changed much over the millennia until the last 50 years.

The anatomy of the male urethra is responsible for the heterogeneity of urethral stricture. Again, urethral stricture disease must be separated from an isolated urethral stricture due to trauma. In such a scenario, a “one size fits all” approach is unlikely to succeed.

It is important to note that most of the evidence for the treatment of urethral strictures come from case series. Randomized controlled trials are almost non-existent.

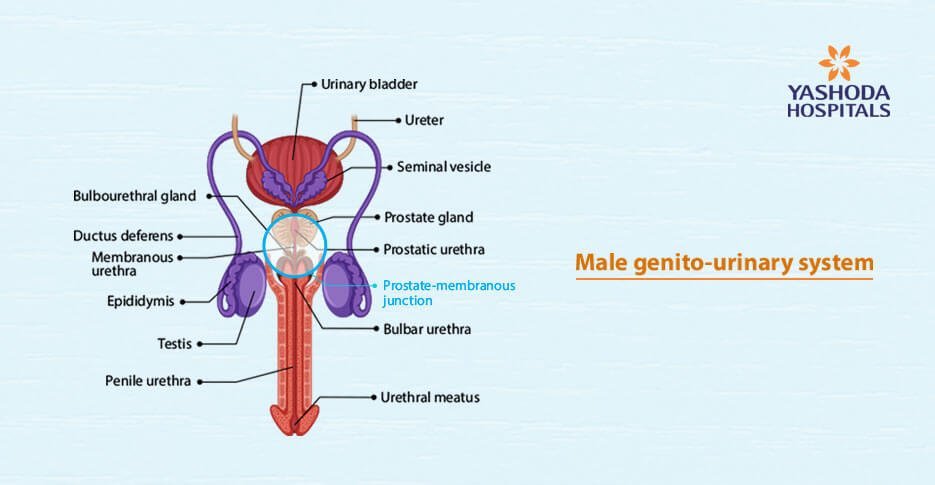

Anatomy – Male genitourinary system

The male urethra originates at the bladder neck and extends to the external urethral meatus. Regardless of what is commonly described, it seems practical to divide the urethra into 2 broad parts – the first consisting of the penile, bulbar and membranous and the second is prostatic urethra. The first part has the spongy “spongiosum” covered by a thin mucosa while the prostatic urethra has prostatic tissue under the mucosal lining, with the transition area being the prostate-membranous junction. Embryologically, the prostatic urethra arises from the pelvic part of the urogenital sinus while the penile and bulbar urethral arise from the phallic part – the urethral plate. The membranous part joins the two.

The classification is important as the response to injury is different in the two areas. Injuries in the penile, bulbar and membranous urethra typically heal with fibrosis- “spongiofibrosis”. The fibrosis is negligible in the prostatic urethra, therefore, transurethral resection of the prostate can be successful.

Urethral strictures vs. Urethral distraction defects

Urethral strictures occur in the anterior urethra. They may be either inflammatory or traumatic. Distraction defects are due to the distraction in urethral injuries that are associated with pelvic fractures. They are situated exclusively in the transition membranous area between the anterior and prostatic urethra. Strictly speaking, strictures of the posterior urethra are never primary. They are the result of failed surgical repair for distraction defects.

Traumatic vs. inflammatory strictures

Trauma to the urethra causes dense spongiofibrosis that usually involves a short segment. The rest of the urethra, both distal and proximal, is essentially normal. These strictures are amenable to excision and primary anastomosis.

Inflammatory strictures may be due to infective (e.g. Gonorrhoea) or non-infective causes (e.g. Blalanitis Xerotica Obliterans). Regardless of etiology, they usually have spongiofibrosis that extends well beyond the actual strictured segment. The spongiofibrosis is less dense than traumatic strictures but extends both proximal to and distal to the narrowed segment. Visually, the mucosa over the diseased segment may be white and metaplastic, and the lumen may have varying degrees of narrowing.

Evaluation

Despite impressive advances in imaging technology, a combination of retrograde urethrography (RGU) and voiding cystouretrography (VCUG) remains central to the assessment of urethral stricture.

For non obliterative strictures, visual inspection of the urethra by cystoscopy with a slender scope can provide information about the extent of narrowing and urethral metaplasia, providing a marker for the extent of spongiofibrosis. On occasion, in the cases of pelvic fractures with posterior urethral distraction defect (PFUDD), antegrade suprapubic tract cystoscopy may be necessary to evaluate the competence of the bladder neck, since it is the primary site of continence after urethral repair.

The role of ultrasonogram (Sonourethrogram) for delineating the extent of spongiofibrosis has been investigated, but its cumbersomeness and its lack of objectivity preclude its regular use. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can offer information about the degree of distraction, lateral displacement, and the presence of nearby bone fragments due to the pelvic fracture. However, it is doubtful that it provides any real advantage over RGU/VCUG for experienced surgeons.

Principles of management

Traumatic lesions

Pelvic fractures with posterior urethral distraction defects and traumatic bulbar urethral strictures

The treatment is standardized and least controversial. Excision of the strictured segment with the surrounding callus is mandatory with anastomosis of the healthy widely spatulated ends (EPA) usually results in a successful outcome. However, though the principles of EPA for PFUDD and traumatic bulbar urethral strictures are similar, the nuances of the technique are significantly different.

Table 1 –Steps of EPA for traumatic bulbar urethral strictures |

|

Mobilization of the bulbar urethra till the penoscrotal junction |

|

Identification and excision of the stricture till healthy urethra proximally and distally |

|

Spatulation of both ends |

|

Corporal plication (if required)* |

|

Tension-free anastomosis with mucosal to mucosal apposition (1 or more layers) |

Table 2 – Steps of EPA for PFUDD- The stepwise progressive perineal approach |

|

Mobilization of the bulbar urethra till the penoscrotal junction # |

|

Identification of the obliterated segment with urethral division |

|

Crural/corporal body separation # |

|

Inferior pubectomy #, identification of the proximal end with excision of all callus |

|

Prostatic mobilization* |

|

Corporal plication* |

|

Supracrural rerouting # |

The steps of corporal body separation, inferior pubectomy and corporal rerouting, though possible, does not help in the repair of traumatic bulbar strictures. The reason is quite simple – by definition, this is a bulbo-bulbar anastomosis; there is a part of the intact bulbar urethra in the proximal segment, particularly during the initial repair. The residual proximal bulbar urethra retains the curve of the original anatomic route and tends to pull the distal end outwards after anastomosis. However, corporal plication and aggressive mobilization of the distal urethra does help in difficult cases.

Distal urethral mobilization, particularly beyond the penoscrotal junction must be balanced by the potential for urethral ischemia and chordee. Stripping of the fascial layer over the spongiosum has also been postulated to further reduce tension during anastomosis.

The transpubic approach ( Waterhouse/Pierce) was quite popular earlier, however, the morbidity is much greater. Since the majority of PFUDD can be managed by an elaborated perineal approach, the role of the transpubic approach is limited to very complex cases.

Inflammatory strictures

The maximum controversy exists regarding the ideal method of management for inflammatory strictures.

Substitution urethroplasty: Traditionally because of the longer length involved in inflammatory stricture, augmentation of the lumen of the diseased urethra with an inlay or onlay segment of flap or graft has been the preferred approach. This has been described as substitution urethroplasty, even though the entire diseased segment is not substituted.

Flaps vs. grafts: Urologists have traditionally borrowed reconstructive techniques from plastic surgeons. Flaps have historically been the preferred method of reconstruction because of their reliability (if well done) compared to grafts. The proximity of hairless skin on the prepuce and the ease of harvest also made it popular. However, increasingly, it is being recognized that a common cause of complex urethral inflammatory strictures is Balanitis Xerotica Obliterans (BXO) which has a tendency to recur on the substituted skin flap. For this reason, in addition to the potential for increased donor site morbidity and almost equivalent results when compared to buccal mucosal grafts have contributed to the decrease in their popularity. Flaps, especially if applied ventrally or as a tube, tend to form diverticula over time with associated complications. The procedure of raising a flap is also more complex than a graft and remains technically challenging.

However for salvage of a long segment urethral stricture or bulbar necrosis, a tubed flap in experienced hands can provide very good results. Secondary manoeuvres can be used to buttress the flap on its ventral surface with additional tissue to prevent diverticula formation. They are also useful in the penile urethra in the case of non-BXO strictures.

Free grafts for the repair of urethral strictures were initially harvested from the prepuceal skin (Presman and Greenfield, 1953)(2). The inner prepuceal skin offers advantages as a graft material for urethroplasty – it is hairless, easily harvestable, and survives well in a wet environment. However, its propensity to be affected by BXO and the superior characteristics of the buccal mucosa has resulted in the lesser use of skin.

Though buccal mucosal grafts (BMG) were initially described in 1886 by Suprechko, it was in 1993 that the initial reports of urethral reconstruction with BMG’s were reported (Burger)(3). They quickly become the material of choice for substitution urethroplasty because of its anatomical characteristics – a pan laminar plexus that facilitates inosculation, imbibition and excellent take. The high elastin content makes it tough and yet easy to handle. The donor site also has minimal morbidity and a concealed scar. Further, it is hairless and does well in a wet environment. While it definitely superior to prepuceal skin in cases of BXO, its advantage in non-BXO cases is not definitely proven.

Staged vs. single stage repairs: Though an effort should be made for single stage surgery whenever possible, complex urethral strictures do better with a staged procedure. It is important to note that 2-stage procedures actually have 3 stages. The middle “interval” stage is important to assess the take of the graft, pliability of the plate, and the patency of the proximal neomeatus before the 2nd stage tabularization.

Ventral vs. dorsal placement of the graft: Ventral onlay graft placement is technically easier and has been reported to have excellent long-term results in western series(4). Dorsal onlay is technically more demanding and requires more urethral mobilization. Spongioplasty remains an integral part of the ventral onlay, which requires good quality thick spongiosum. Extensive urethral disease and the relatively narrower urethra in the Indian population may not allow for a wide ventral graft after spongioplasty. It is best reserved for cases with a very short segment mid to proximal bulbar strictures (in the area covered by the bulbospongiosus muscle). In all strictures with longer length, distal extension to the penile urethra, and a thin bulbar urethra, a dorsal onlay is preferable.

Penile urethral strictures

Short segment penile urethral strictures may be simple to repair if the rest of the urethra is normal. However, in cases where the entire penis is involved by BXO, it is technically challenging. Staged substitution procedures are generally preferred.

Definitive perineal urethrostomy: In the case of multiple failed surgeries – “urethral cripple” in an older patient – a definitive perineal urethrostomy may be an excellent option. It is important to place the broad tip of the perineo-scrotal flap as proximally as possible. Addition of a dorsal only graft to the ventral perineal flap may offer greater rates of patency and fewer reinterventions.

Redo-urethroplasty: Redo-urethroplasty remains challenging and is best left to specialist urethral surgeons. The concern in redo anastomotic urethroplasty is two-fold:

- Adequate length of the residual urethra to permit tension-free anastomosis

- The vascularity and viability of the distal urethral segment

Complete excision of callus requires extensive dissection between the prostatic urethra and the rectum. A more elaborate perineal approach, including inferior pubectomy is usually required in these cases. Occasionally, it may not be possible to achieve a tension-free anastomosis with the perineal approach, in which case, intraoperative conversion to a transpubic approach should be done. In inflammatory strictures, a redo substitution urethroplasty is usually possible – either by a ventral onlay or dorsal inlay approach.

Urethral rest before urethroplasty: Recent urethral instrumentation (within 30 days) those on intermittent self-calibration at presentation are deemed to have unstable strictures. Waiting 6-8 weeks will allow for remodelling and permit the exact location and severity of stricture to be known. A suprapubic cystostomy may be placed if indicated (5).

Endoscopic internal urethrotomy (EIU) for urethral strictures: The long term success rate for endoscopic internal urethrotomy is poor. It may be used in short segment urethral strictures with minimal spongiofibrosis. There is no evidence to suggest that injection of steroidal and anti-proliferative agents at the incision site increases the success rate.

Conclusion

Urethroplasty requires experience and knowledge of a wide variety of techniques. There is no single correct technique and surgery may need to be individualized for the particular patient. It is best that the surgeon brings a bouquet of skills to the table and adapt according to the stricture.

Note: This is an extremely personal view of a complex subject. Readers will be best served if they put on their “reconstructive hats” while reading this.

References:

- Barbagli G, Montorsi F, Guazzoni G, Larcher A, Fossati N, Sansalone S, et al. “Ventral oral mucosal onlay graft urethroplasty in nontraumatic bulbar urethral strictures: surgical technique and multivariable analysis of results in 214 patients”. Eur Urol. 2013 Sep;64(3):440–7.

- Barbagli G, Sansalone S, Djinovic R, Romano G, Lazzeri M. “Current controversies in reconstructive surgery of the anterior urethra: a clinical overview”. Int Braz J Urol Off J Braz Soc Urol. 2012 Jun;38(3):307–16; discussion 316.

- Bürger RA, Müller SC, el-Damanhoury H, Tschakaloff A, Riedmiller H, Hohenfellner R. “The buccal mucosal graft for urethral reconstruction: a preliminary report”. J Urol. 1992 Mar;147(3):662–4.

- Terlecki RP, Steele MC, Valadez C, Morey AF. “Urethral rest: role and rationale in preparation for anterior urethroplasty”. Urology. 2011 Jun;77(6):1477–81.

- Webster GD, Ramon J. “Repair of pelvic fracture posterior urethral defects using an elaborated perineal approach: experience with 74 cases”. J Urol. 1991 Apr;145(4):744–8.

Appointment

Appointment WhatsApp

WhatsApp Call

Call More

More